Disorder, Entropy, and Couette

Flow

Ever since the statistical interpretation of

entropy became popular, more than a century ago, students have been

taught that entropy tends to favor a state of greater disorder over a

more ordered state, and that the inevitable increase in the entropy,

or disorder, of the universe provides a direction for time.

A typical example is found in Richard Feynman's

discussion of irreversibility [The Feynman

Lectures on Physics,Vol. I, 46-7], where

he uses italics to emphasize:

"It is the change from an ordered

arrangement to a disordered arrangement which is the source of the

irreversibility."

The truth of this sort of statement hinges on a

proper understanding of what is meant by

"a

disordered arrangement," a meaning that may not be obvious to a na´ve

reader and is not always clarified (Feynman does address it

several paragraphs later, see answer below).

|

One approach to a proper understanding of

order and disorder is to consider a scientific parlor trick

(one that is often analogized to spin- or optical-echo

experiments). The demonstration involves

Couette

flow of a viscous liquid in the

space between two coaxial cylinders.

|

Click to see

the whole experiment (2 meg)

|

Cross Section

|

On the right is the first frame from a

movie showing the spreading of a yellow dye in a viscous

liquid (shown blue in the cross section on the

left). The liquid is held between a

stationary interior rod and a rotatable glass

tube.

In the movie the outside tube is rotated

to the left by three complete turns, 3 x 360░ =

1080░ (note black reference line)

and then rotated back again.

Click

to download the QuickTime movie (0.9

meg)

|

Compare the last frame of the movie

to the first frame. Only the time on the watch has

changed.

(The watch proves that there has been no software

hankypanky.)

|

At first this seems quite surprising.

Because the liquid appears uniformly yellow after rotation, it is

natural to assume that the dye has been randomly and uniformly

mixed throughout the liquid. "Unmixing" should be impossible, as

is pointed out by the 13-year-old prodigy Thomasina to her tutor

Septimus in Tom Stoppard's 1993 play "Arcadia":

|

THOMASINA: When you stir your rice

pudding, Septimus, the spoonful of jam spreads itself

round making red trails like the picture of a meteor in

my astronomical atlas. But if you stir backward, the jam

will not come together again. Indeed, the pudding does

not notice and continues to turn pink just as before. Do

you think this is odd?

SEPTIMUS: No.

THOMASINA: Well, I do. You cannot stir

things apart.

SEPTIMUS: No more you can, time must

needs run backward, and since it will not, we must stir

our way onward mixing as we go, disorder out of disorder

into disorder until pink is complete, unchanging and

unchangeable, and we are done with it for

ever.

|

Cross Section after 1080░ rotation

|

In fact the flow of the viscous liquid is, to a first approximation, laminar and without turbulence, inertial flow, or

diffusion. The amount of angular displacement of any bit of

liquid depends only on its distance from the axis of the

cylinders. The liquid has been cleanly sheared.

Bits of liquid next to the rotating outer

cylinder rotate with it by 1080░, while those next to

the stationary inner cylinder do not rotate at all. After

three cycles of rotation the dye forms a thin sheet wound

three times around the cylinder axis (as shown by the red

line in the cross section at the left). Viewed from the

side, the dye appears to be evenly distributed, because from that perspective we

cannot perceive the pattern.

Reversing the rotation "unwinds" the

spiral sheet back into the original line.

[Of course this kind of non-turbulent

"mixing" does accelerate true dissolution by shortening

the distances that need to be covered by randomizing

diffusion, but diffusion in a liquid as viscous as corn

syrup is very slow.]

|

What fooled us was the appearance of randomness after

1080░ rotation. The dye was just as ordered after rotation as

it was before, but in a less easily perceived way.

|

This Couette flow demonstration makes us

cautious about supposing that an arrangement is random or

"disordered" just by the look of it. What appears to be

disordered may truly be ordered but in a very complicated

way.

Of course one can arbitrarily define some

quantitative measure of the randomness of a distribution

(e.g. the fractal dimension), but different individuals

could choose different measures.

In fact any arrangement at all might

be considered "ordered" by someone.

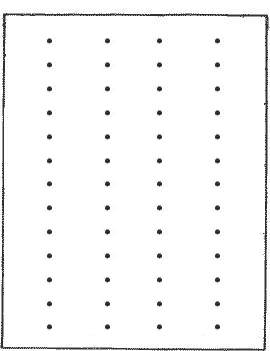

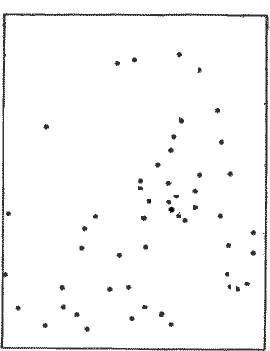

Compare the two sets of 52 dots in the

frames to the right. Most individuals would think of the

second arrangement as rather disordered, but you can

click

here to see that the second is also highly

ordered.

|

|

|

If any arrangement may be considered ordered -

if order is in the eye of the beholder - the concept of "a disordered

arrangement" is an oxymoron and dangerous to use in a fundamental

theory.

|

What did Feynman mean by

saying,

"It is the change from an ordered

arrangement to a disordered arrangement

which is the source of the

irreversibility."

|

|

After thinking about this riddle for

a while, click

here for the

answer.

|

References

Reversible Couette Flow as a model of spin

and optical echos is discussed by R. G. Brewer and E. L. Hahn, in

"Atomic Memory", Scientific American, 251, No. 6, pp.

50-57 (December, 1984) [thanks to Victor Batista

for this reference]

For a more physical description of the Couette unmixing experiment

see John P. Heller "An Unmixing Demonstration," American Journal

of Physics, 28, 348-353 (1960).

Tom Stoppard, "Arcadia", Faber and Faber, Boston, 1993. Act I,

Scene 1. [Thanks to J. D. Dunitz for pointing out

this passage.]

Dinosaur connect-the-dots from http://www.lizardpoint.com/fun/java/dinodots/dino1.html

Thanks to Angelo Gavezzotti, Kurt Zilm, and John Tully for

helpful comments.

copyright 2002

J.M.McBride